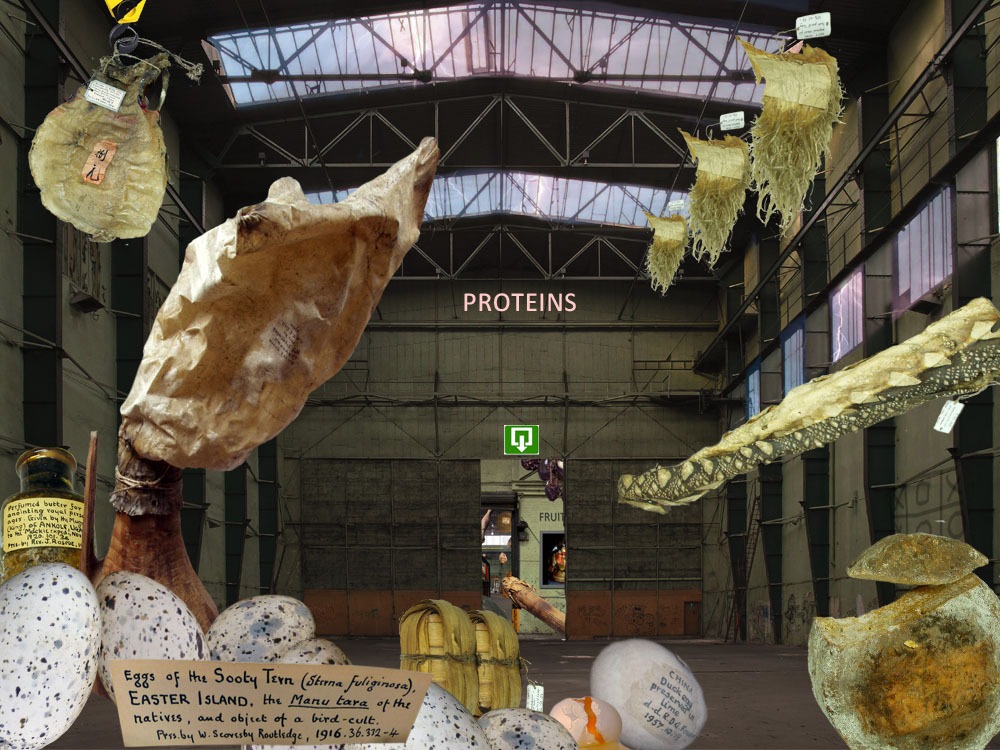

PRM Inv. nr. 1957.10.18-19

Duck eggs preserved in lime

China, 1957

Len Fisher: Duck eggs preserved in lime

Given the date of collection, these are likely to be the real deal. Also known as pidan , century eggs, millennium eggs, and one hundred year-old eggs, the preservation process actually takes about five months. Hundred year-old eggs deserve a hundred year-old recipe, and here it is. The recipe, provided to the authors by the manager of an unspecified Chinese factory, was first reported in the West by the American food chemists Katharine Blunt and Chi Che Wang ( Journal of Biological Chemistry 28 (1916) 125 -134), who also analyzed the product in what some might consider to be excruciating detail. To an infusion of one and one-third pounds of strong black tea are stirred in successively 9 pounds of lime, 4 pounds of common salt, and about one bushel of freshly burned wood ashes. This pasty mixture is put away to cool overnight. Next day 1000 duck’s eggs of the best quality are cleaned and one by one carefully and evenly covered with the mixture, and stored away for 5 months. Then they are covered further with rice hulls, and so with a coating fully inch thick are ready for the market. They improve on further keeping, however, for at first they have a strong taste of lime which gradually disappears. ...The eggs are eaten without cooking. "These are very different from fresh eggs” the authors go on to say. "The somewhat darkened shell has numerous dark green dots on the inner membrane. Both the white and yolk are coagulated; the white is brown, more or less like coffee jelly, and the yolk greenish gray with concentric rings of different shades of gray. The yolk gradually loses its peculiar color on exposure. Numerous tyrosine-shaped crystals are found on the side of the white next to the yolk, apparently formed on the vitellin membrane. The taste of the eggs is characteristic and the odor markedly ammoniacal. It may be noted here that the eggs have no odor of hydrogen sulfide and that no blackening of lead acetate paper [a test for hydrogen sulfide LF] could be detected ...”

What the marinade is doing, in technical terms, is to denature the egg proteins, so that the string-like molecules become entangled and form an elastic gel, whose properties have even been compared to those of the amyloid plaques associated with Alzheimer’s disease (Erika Eiser et al: “Molecular cooking: physical transformations in Chinese’century’eggs” Soft Matter 5 (2009) 2725 -2730).

Not to worry! You are eating it, not injecting it into your brain. Pidan, properly prepared, is a tasty (and safe) delicacy, but it's better to eat the museum specimens, rather than risk the present-day commercial product, where things have been speeded up. As the author pointed out in a talk at the 2007 Oxford Symposium “Food and Morality”, the product is likely to have been immersed in caustic soda, rather than gentle lime, potash and tea, and to have taken a week to prepare rather than five months. The end product is superficially similar, with the proteins in the egg having been denatured by the gradually increasing alkalinity as the components of the unusual marinade diffuse into it, but there the similarity ends. The taste is altogether harsher, and the experience correspondingly less pleasant.

The experience might even be fatal. One Chinese factory, now fortunately closed down, was recently found to have been adding poisonous copper sulfate to the mixture in order to enhance the colours! (https://qz.com/94864/preserved-thousand-year-old-

eggs-in-china-are-even-more-toxic-than-they-sound/)

The colourful sliced eggs may be served as part of a salad, but the real deal makes a real meal.

PRM Inv. nr. 1920.101.36

Glass bottle sealed with red wax with perfumed butter for anointing royal personage .

Uganda. Cultural Group: Nkol, 1920

PRM Inv. nr 1899.45.6

Sturgeon skin used for food.

Strip of sturgeon skin folded in half length ways and dried.

Japan, Hokkaido,(Ainu) 1899.

Len Fisher: Sturgeon skin used for food

The Ainu people from the Japanese island of Hokkaido call the sturgeon kamuichepu (fish of the gods). It was thought to be the presiding god of the river that is now called the Ishikari, and it is certainly a gift from the gods so far as the Ainu are concerned. They even use the skin to make clothes and bags. As the label on the exhibit in the Pitt-Rivers museum indicates, they also eat it.

According to Japanese food writer Makiko Itoh, the skin is usually blanched and sliced into thin strips, where the chewy texture is much prized by aficionados. Pieces of sturgeon are also salted and smoked with the skin on, where the combination of fat and collagen produces interesting textural and taste effects. The same may be said of the small fish that are sun-dried in India and Bangladesh to produce “Bombay Duck.”

The Ainu are not the only people to incorporate fish skin into their cuisine. Food writer Elisabeth Luard points out that toasted salmon skin, with its underlayer of fat, is traditionally eaten with gravlax in Norway. Moving further afield, fish skin (including sturgeon skin) can also be used in place of pig skin to make a fishy version of the Mexican chicharron – crispy, light as air and oddly ungreasy.

Sturgeons are, of course, the source of caviar – the salt-cured “roe of the virgin sturgeon”, as the popular song puts it. The quality varies with the species of sturgeon, and there are 27 different species across the world. The particular species from which the Pitt-Rivers skin specimen was obtained seems to have been the Sakhalin sturgeon, endemic to the Sea of Japan and the Korean Peninsula, and now listed as critically endangered (although “Sakhalin caviar” is still sold by some suppliers). It is relatively expensive, perhaps because of rarity, but not comparable in quality with the famous beluga caviar, obtained from the beluga sturgeon Huso huso, which is found primarily in the Caspian sea.

Most of the world’s caviar now comes from farmed sturgeon, where the mature females produce tens of thousands of eggs in a batch. There is a sporting chance that the sturgeon from which the Pitt-Rivers skin specimen was obtained was a female, captured mainly for her eggs, and an admittedly much smaller chance that some of those eggs may have become stuck to this piece of skin. With tens of thousands of eggs, each surrounded by sticky membranous material, produced by a gravid mature female, surely there was some chance?

We thus have two potential food sources from the Pitt-Rivers specimen – the skin itself, and any roe that may have become stuck to it.

PRM Inv. nr. 1906.58.54

Pudding made from coconut milk wrapped in palm leaves.

Ellice Islands, Funafuti, 1906

PRM Inv. nr: 1916.36.332

Three Sooty Tern eggs, alltogether in a museum display box.

Easter Island Rapa Nui. Motu Nui (islet near Easter Island)

Chile 1916

The Tangata manu or "bird-man" was the winner of a ritual on Rapa Nui (Easter Island). The ritual was an annual competition to collect the first sooty tern ( manu tara ) egg of the season from the islet of Motu Nui, swim back to Rapa Nui and climb the sea cliff of Rano Kau to the clifftop village of Orongo.

“On page 265 of collector's published account of the expedition to Easter Island, Katherine Routledge writes: 'The tara departed from Motu Nui about March, but a few stragglers remained; we saw one bird and obtained eggs at the beginning of July'. The 'Bird Cult' associated with the collection of sooty tern eggs is described on pages 254 to 268. See Mrs. [Katherine] Scoresby Routledge (1919) The Mystery of Easter Island: The Story of an Expedition. London: Sifton, Praed & Co. Ltd. “

PRM Inv. nr. 1886.12.2

Reindeer milk cheese,

Norway (Finnmarken) 1886

T.G. Smollett remarked upon it in 1775:

“The cheese made of reindeer-milk is eaten new, or boiled in water and stored up, and sometimes toasted. It is so fat as to burn like candles, and said also to be an excellent specific to restore limbs benumbed with cold.”

From: Memoirs of the Laplanders in Finmark, their Language, Manners, Customs, and former Paganism, &c.

Smollett, T.G. (ed.). The Critical review, or, Annals of literature; London Vol. 40 (Nov 1775). P.395

PRM INv. nr. 1914.27.7

Swim bladder from the Yellow-bellied Wong fish.

“Used as food and also for making glue for composite bows”

Soochow , China 1914

Swimbladders in Iceland foodculture - Notes from Nanna Rögnvaldardóttir

Swim bladders were boiled until soft and preserved in fermented whey or in some skyr. They are a rich source of isinglass and if a bladder was parboiled briefly, then put into a bowl of skyr while still hot, the skyr coagulated and could be cut into slices. Sundmagaskyr was considered a delicacy.

Although isinglass was widely used in jellies and desserts before gelatin became popular, I’m not sure if swim bladders were ever used as a dessert by themselves anywhere else but there are Icelandic recipes for whey-preserved swim bladders, cut up small, caramelized in sugar and served with whipped cream.

Dried swim bladders could be soaked in salted lamb broth overnight, then cooked in butter. Milk was added, along with some flour, to make a gluey mass, called sundmagasteik,swimbladder steak. One source tells of a woman who made what she called swim bladder cheese

by cooking a large amount of barley porridge and arranging it in a barrel in layers, alternating

with swim bladders.

Fish bladder from the yellow bellied Wong fish - Notes from Len Fisher

The bladder is “yellow in colour and roughly oval in shape with curled over edges” (and roughly 27cm long). It hardly seems like material for a food delicacy, but you couldn’t be more wrong.

The swim bladder is an internal gas-filled organ found in most fish, which use it for flotation. It is composed of collagen, a triple-stranded protein that makes up most of the connective tissue in our bodies. Collagen is difficult to digest, but when heated with water it turns into gelatin, whose uses in food preparation are numerous.

The collagen from swim bladders seems to be rather special. It is particularly valued in South-East China and South-East Asia as a primary component of fish maw soup, a delicacy that is especially associated with the Chinese New year. It is also the favoured source for isinglass – a semitransparent whitish form of gelatin that is used to clarify beer and wine, to preserve eggs in their shells, and even as a specialist glue for paper conservation and for violin bows, where flexibility needs to be combined with strength.

Isinglass can also be formed into thin flexible transparent sheets and used as a curtain material. The Hollywood actor Gordon McRae even sang about it in the film Oklahoma, where “The Surrey With The Fringe On Top” had “Isinglass curtains you can roll right down, In case there’s a change in the weather.”

But we digress. There are a number of different ways to prepare and eat fish bladder. Most of them require that the bladder (which is usually available only in dried form, as with that of the Wong fish, although most have not been dry for quite so long) be rehydrated by soaking in water for a couple of hours. It is then pat-dried, and can be added directly to a fry-up.

The most significant use, though, is in the highly prized fish maw soup. In what is called the traditional method (Sittichoke Sinthusamram & Soottawat Banjakul “Effect of drying and frying conditions on… characteristics of fish maw …”, Journal of Science of Food and Agriculture 95 (2014) 3195-3203) the whole bladder is fried in vegetable oil until it puffs up, then sliced up and added to the soup as in the Festive Fish Maw Soup below. Other recipes, however, incorporate the bladder without frying, as in the Nyonya recipe (the cuisine of the Peranakans, descendants of early Chinese migrants who settled in Penang, Malacca, Singapore and Indonesia). Take your pick!

PRM INv. nr. 1896.62.97

Dried shark’s fins,

China, 1896

PRM Inv. nr. 1900.12.1

Butter churn comprising a lamb skin with wooden funnel

France 1900